“Big Data” analysis has often seen applications toward bettering already well-integrated systems; it is usually leveraged as a strengthener for pre-existing infrastructures rather than as a tool for building frameworks from scratch. The latter application has recently been surging as a way to disrupt industries and dated methodologies, and Mauricio Santillana’s topic belongs in this group: analyze the endless stream of social media in order to prevent critical dangers—specifically outbreaks of communicable diseases—in the world.

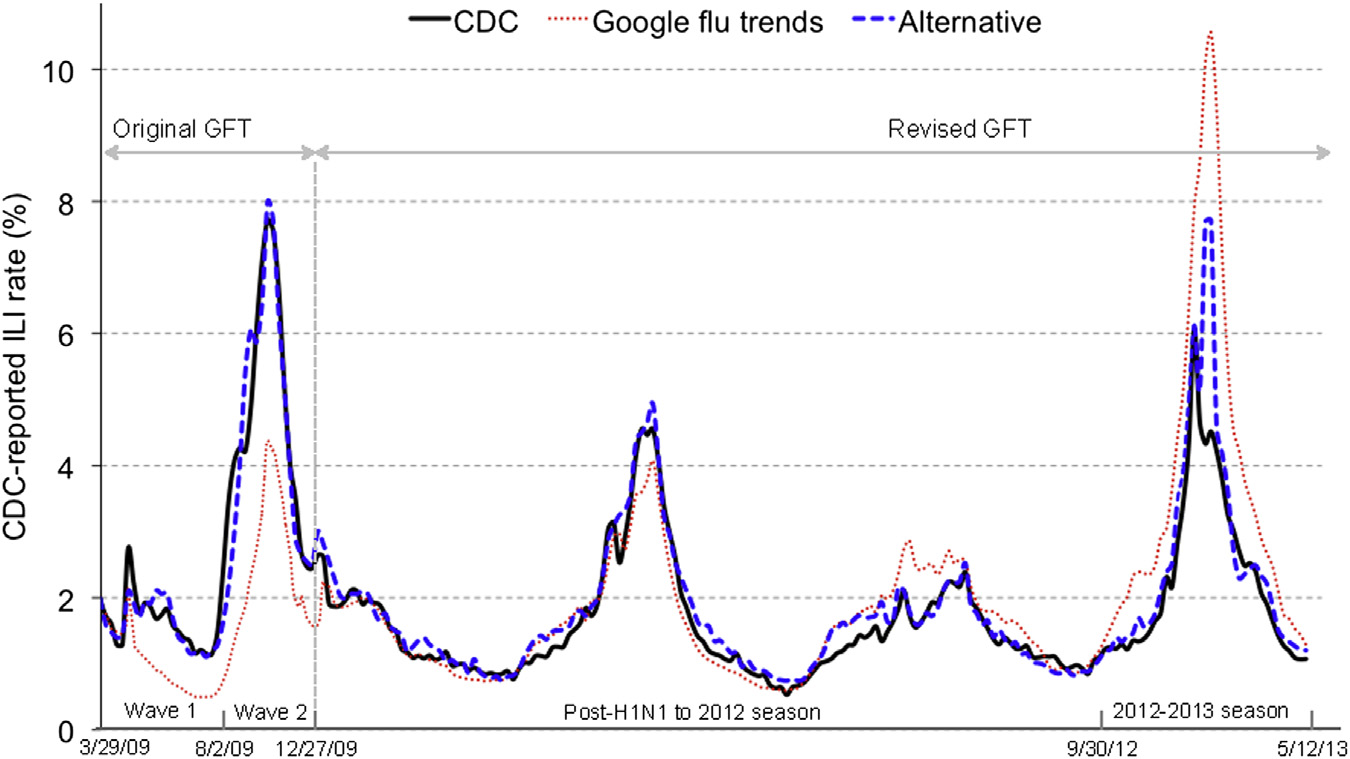

It’s a noble idea, and one absolutely crucial given that the current alternative is to wait weeks before any officiality hits the news. Google Flu Trends has already tried modelling this with relatively poor success [1], leading the media to have its doubt about the success of such a model.

The revised model proposed by Santillana et. al [2] is surprisingly simple: take the most correlated search terms from Google, use them as your parameters, run LASSO regression, and that’s it. Not only is the performance improved with lower mean squared error, the data that was used to construct the revised models is much much smaller than the original’s (only 5 weeks of data compared to the span of many years). What’s perhaps more surprising than the simplicity of the model is how Google didn’t think of this before. It is peculiar that the previous GFT (Google Flu Trends) model was based on univariate analysis instead, where the single input is an aggregate of all the correlated search terms. This leaves zero room for any weights assigned to each parameter, from which the model can then assign and better account for error. The features included in GFT were also human curated rather than collected empirically (what a red flag!).

Given that the model produces a continuous stream of numbers, it would be useful to build an ROC curve in order to weight more against false negatives than false positives. After all, it seems more important that we do not fail to report an outbreak, rather than to report outbreaks that don’t actually happen. It would then be trivial to determine a cutoff (as well as some credible/confidence interval) in order to report just how statistically significant our belief is.

Another natural consideration is to further improve performance by testing other algorithms (SVMs most come to mind). It seems the significant change in the revised approach is the multivariate consideration, and having had the pleasure to speak with Mauricio personally, there isn’t actually any reason why to stick with LASSO. It was only a good first choice given sparsity reasons from the norm.

Further yet, why even use only queried search terms from Google and not other sources, or not integrate other well known and important variables? Several features currently reported significant to the model seem only to do so because they’re highly correlated with something else, such as seasonal changes. Hence, instead of including a search term such as “gymnastics meet” which would only act as a proxy for time, we may as well include time itself.

We also have knowledge a prior that modelling based on search terms is bound to exaggerate the output of maximum values of the function given compounding media hype. If more sources are ever added we can attempt to balance these through an extra layer of added weights assigned to the source.